New Part, New Trends

Guestimation time, as promised in Part I. After our 2020 retrospective, we now move onto the new trends for 2021 impacting rightsholders in the sphere of counterfeiting and piracy. As always, a brand should not be considered synonymous with an intellectual property right, or indeed a marketing campaign. A brand acts as a mental patent, therefore any factors concerning the underlying inventiveness of the brand must be incorporated into the brand protection strategy. Therefore the factors in scope are wide-ranging: covering intellectual property rights, legal and regulatory frameworks, brand personality, social media management, domain name management, security related issues and so much more. To learn about the so much more, see Digital Brand Protection, specifically Chapter 2: A Strategic Approach. In this year’s edition we chart a spectrum of trends covering podcasts to competition law.

Influencers x Brand Protection

The cycle will be broken. Influencers will learn the value of brand protection. For years Instagrammers, YouTubers, and now TikTokers have focused solely on building – building an audience, a brand, a community. 2021 will be the year influencers appreciate the value proposition of brand protection – registering intellectual property rights and enforcing them. It may be trite to say, but case after case has demonstrated the point: influencers generally have a negative view of intellectual property. Many only know copyright, and that it can be used by larger companies to remove their posts, videos, and content. There exist endless examples of takedown requests based on trade mark infringement being called out as ‘copyright abuse’ from online influencers.

It is time, and the conditions are right, for influencers to break out of this narrative. Most influencers with strong communities are business savvy, understanding the importance of developing a strong brand. What will change is the appreciation of doing due diligence to ensure their brand is actually a brand, and not just a recognisable internet persona. For example, many influencers rely on meme culture for slogans, merch designs, content etc. however, shrewd influencers are learning that a brand requires distinctiveness, therefore spending time to develop a uniquely authentic slogan is an investment.

A typical YouTuber goes from wanting a large audience to generate ad revenue, then realising ad revenue on the platform has been depressed for at least 8 years now.[i] They then branch out into other means of boosting income, usually through sponsored videos or ads. They maybe add a Patreon account for “donations”, maybe livestream to generate additional revenue, or maybe use affiliate links. The smartest influencers grasp the situation, seeing the opportunity to use their platform, their audience; not to sell goods for other brands, but as an opportunity to sell their own. Usually, this is in the form of merch. But for certain categories – make-up, ‘health’ supplements, and toys the most common – the influencer is better off developing their own line of goods. This approach empowers the YouTuber to leverage their millions of subscribers and hundreds of hours of viewtime per month for their own benefit.

This has been happening for years now. Most rush out a launch by slapping a popular design recognisable to their community onto T-Shirts, hoodies, hats etc. through a platform such as Redbubble, Teespring or some other third-party service which ends up extracting more value than the YouTuber. There are also examples where a full-fledged clothing brand has been launched, either from the outset or after a redesign following the realisation of the opportunity at hand.[ii]

Even relatively small influencers notice the deluge of counterfeits that follow their launch. With counterfeiters copying designs from teaser videos and launching before the influencer’s own product reaches the market. It is not only the large brand who suffer from counterfeiting. Infringers care about profit making opportunities, not the brands they victimise. Therefore, if copying the designs of an influencer with a dedicated community will turn a profit, the design will be copied. And they are being copied, mercilessly.

However, the issue is not confined to anonymous pirates unlikely to see justice anytime soon. Influencers are having their brand assets appropriated by mainstream brands and retailers. Companies frequently dip into online culture, meme culture, when searching for content for marketing campaigns and new releases. Often, they fail to spot the difference between widespread memes and a turn of phrase distinctly associated with a specific influencer. The ‘if it’s not registered I can use it’ approach is not adequate due diligence, not from small influencers without any knowledge of intellectual property, and certainly not form large brand owners and retailers.

Too many successful influencers with a committed following are inadvertently sharing their profits, reputation, and goodwill with third-party companies. Influencers will not only want to protect their brand, but also protect the community they worked to build through hours of content creation, audience engagement, and years of hard work. What will be done – influencers will start focusing on developing distinct brand assets, exclusive to their brand and authentic to their brand personality, registering rights, monitoring for infringements, and enforcing their rights.

Podcast Piracy

In 2019 Spotify signalled a shift, the company no longer wanted to be seen as a music streaming platform, instead an audio streaming platform.[iii] To the ire of the music industry,[iv] the humble podcast was to direct Spotify’s customer acquisition strategy. Before acquiring new customers, Spotify spent big on snaping up other podcast platforms and portfolios. After laying the groundwork Spotify could then focus on the eye-catching deals in 2020. Spotify is now the exclusive home to the podcast of Michelle Obama,[v] Joe Rogan,[vi] Kim Kardashian West,[vii] and the ‘Sussexes’.[viii] Joe Rogan’s deal was reportedly worth over $100 million.[ix] All from the genesis of a hobbyist cottage industry.

With Spotify’s aggressive podcast strategy the European streaming service has again outfoxed main rival Apple. The reason behind Spotify’s investment in the podcast industry, is because podcasts just work. Compared to music licensing, podcasts are cheaper, more predictable, and streaming platforms are not beholden to entrenched media conglomerates.[x] For music, Spotify pays a royalty for each stream, estimated around $0.0044 to $0.0084 per stream when the listener plays at least 30 seconds of the song. There are however plenty of real-world examples of artists publicly criticising the royalty rate they receive at the end of the chain. A remedy was to allow independent artists to upload music directly to the catalogue; in theory generating higher royalties for artists by cutting out the middlemen. The foray failed, serving only to worsen the relationship with the music industry, who felt usurped by the attempt.[xi] A new direction was needed.

Enter the podcast. As Spotify founder Daniel Ek explained, podcasts “shift cost base from variable to fixed”, a win for the platform. Another win is the fixing of engagement time; a few poor recommendations from the algorithm could see music streamers turn away to another platform, app, or activity scrapping for their attention. Podcast listeners are captured for a risk-free hour when the latest episode of The Joe Rogan Experience is released.

Generally podcasts provide strong revenue streams for the podcasters, typically through selling ad slots. Major podcasters will receive enormous licensing deals, smaller podcasters and potential new entrants can fairly monetise their works. It’s easy to see why Spotify is so heavily invested in the space. Although music is not being abandoned, it must be nice for Spotify to find a revenue stream whereby both the creators and platform are happy – and without the weight of the 800-pound music industry gorilla to deal with. Of course, not all creators are happy with the exclusivity contracts, outspoken rapper-turned-podcaster Joe Budden has hit out against Spotify.[xii] On balance, losing The Joe Budden Podcast is less of a headache than high-profile spats with Jay-Z[xiii] or Taylor Swift.[xiv]

How to protect this new darling – to love and to cherish to the exclusion of all others. Spotify’s mega-deals all contain exclusivity provisions. Michelle Obama’s podcast did get distributed through other providers, but only after the full season had been aired exclusively on Spotify.[xv] This tactic is to uncover potential customers from other platforms, migrating them over when the new season airs with all the surrounding hype. Fresh episodes and an enviable library equal fresh new Spotify Premium subscribers.

With exclusivity comes a motivation for infringement. As discussed in context of audiobooks and YouTube, DRM circumvention software is widely available and advertised all over social media. Spotify is not immune from software targeting the platform. As we said before:

“the issue is the ease in which audiobooks are being uploaded to YouTube, and the ease in which they can be downloaded. File-sharing is like toothpaste, once it is out of the tube it can never be put back in, rightsholders only play is to try cleaning up the mess.”

Listeners who have followed their favourite podcast on YouTube for years will be hardest to migrate over to Spotify, if they don’t already have a premium account. Exclusive podcast episodes are being ripped and uploaded to YouTube almost immediately after airing. Some websites have even taken to posting the entire episode transcript masquerading as an article or review of the episode. Spotify will have to enforce against podcast piracy across the entire digital supply chain. Not only highly visible endpoints such as YouTube, but taking measures to strengthen DRM and enforcing against software enabling circumvention. Fortunately for Spotify, claims against DRM circumvention software should be easier to win then for a platform such as YouTube; Spotify are unlikely to face the ‘preserving digital evidence’ excuse.[xvi]

Shopify Taken Seriously

No mention in the counterfeiting and piracy watchlists from the EU and US.[xvii] Not surprising given only 3 submissions made to the European Commission recommended Shopify for inclusion, out of over 100 submission documents. Another oddity is out of the 3 recommendations, 2 of the submissions were from entities focused on streaming piracy. The other request for inclusion was from the wonderfully detailed submission provided by UNIFAB, listing Shopify as “Priority 1” platform. Another peculiar turn of events is this categorisation was seemingly based off a single referral from a UNIFAB member “In 2019, Shopify skyrocketed into prominence and came onto one of our members’ radar. Many infringing sites have been notified for takedown”. Shopify was largely absent from popular IP news sites, with a passing mention of the platform in a World Trademark Review article about the best that is on offer.[xviii] Clearly, Shopify is not an issue for rightsholders…

Except a marketing report by FakeSpot reportedly identified 26,000 Shopify webstores related to fraudulent practices representing a variety of brand risks. FakeSport only reviewed a sample of 124,000 Shopify webstores.[xix] The brand risk most prevalent was the sale of counterfeit products. So the question must be asked – how has this gone unnoticed by rights holders, trade associations and brand protection vendors? Why did not a single vendor include Shopify in submission? How comes only a single trade association focused on product counterfeiting included Shopify? Even the usually reliable BASCAP (Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting and Piracy as part of the International Chamber of Commerce) fail to identify the issue.

The Financial Times and BBC both picked up on the FakeSpot story, so it is likely to now be on the radar of rightsholders. Maybe, Shopify wasn’t a major issue previously but has suddenly rose to prominence over the course of 2020?

In August 2020 the Financial Times reported “Now bigger than eBay, Shopify sets its sights on Amazon”, charting the value of Shopify’s shares which had become more valuable than “Twitter, Square and Spotify” since being listed in 2015.[xx] In June 2019 we wrote an article detailing the abuse of Shopify stores within dropshipping, and when I Chaired the 6th Global Brand Protection Innovation Programme later that month had this to say on the platform during a keynote presentation:

“Dropshipping also connects to this. Using the services of Shopify or other webstore builders, an infringer can very easily make their own store. This can be done almost without cost. Most will pay small fees for the added benefits, but in less than a day a webstore can be up and running, fully customised and largely automated, using applications such as Oberlo. What this enables is for any infringer to have their own webstore, a customer goes on it, sees the address is Europe or the US and places the order thinking the webstore is trustworthy. That order actually goes directly to AliExpress, through the automation applications. The AliExpress seller ships it directly to the customer, the webstore owner never touches the product – they do relatively little. Their only goal is to drive traffic to the webstore, mainly is through digital advertising, specifically on Facebook. Customers that would normally worry about buying a fake item from AliExpress will see something pop up in their social media feed being advertised from a creditable looking webstore and are induced into purchasing. They actually purchase at an inflated price, for an item they customer would typically avoid on AliExpress! From research conducted by Ustels, using analytics on popular Shopify webstores offering for sale counterfeit items, infringers can generate revenues of seven figure sums per year. This is just infringers marketing counterfeits, importing them from China and using small packet delivery to avoid enforcement through customs.” You can read the full keynote here.

We know Shopify is involved somehow in dropshipping, but what is the platform? From Digital Brand Protection, published November 2019:

“Shopify is a webstore builder and ecommerce platform which has grown rapidly, becoming one of the strongest rivals to Amazon in the west. To be clear, Shopify is not a marketplace. Investigating Shopify webstores is difficult as traditional domain and website investigative techniques point only to Shopify, and not to the direct infringer. It is difficult to get personal identifying information from Shopify regarding brand abusers. However, one of the reasons Shopify has grown so popular is due to integration with AliExpress, Amazon and eBay. As mentioned in the dropshipping case study above, many Shopify stores simply use AliExpress listings. Illicit Shopify webstores will often attempt to automate processes in order to minimise ongoing resources needed to maintain the webstore. This enables an investigator to use reverse image searches to detect other instances of the same listing, including on marketplace platforms. Also, using BuiltWith, the tool can quickly display which plugins are being used, from which the investigator can infer which platforms the infringer also utilises. Detecting all components of the digital supply chain is vital; Shopify should be used as a tool to uncover merchants on other Shopify webstores, Alibaba platforms, Amazon, eBay, Facebook or any other online platform. An approach which only uses notice and takedown will result in Shopify removing the infringing product listing, but extremely rarely will the webstore be suspended or a repeat infringer banned. A strategic approach yields intelligence.”.

We also mentioned Shopify in last year’s predictions:

“Stronger terms of services and reporting mechanisms leads to infringer displacement. Shopify has been eating away at Amazon and other marketplaces, offering better margins for merchants and dropshippers. eBay saw somewhat of a mini-revival over the Christmas period in terms of brand piracy as merchants seek pastures new. Numerous dropshipping platforms are offering guidance and automation to ‘avoid VeRo takedowns’, softening the departure from the west’s dominate marketplace. As such, less-regulated platforms are likely to benefit once infringers wise up to the false claims. Shopify and Wish are likely to be the biggest beneficiaries over the course of next year.”

Shopify was indeed a main platform merchants forced off Amazon migrated towards. Although it would be to downplay the success of Shopify to suggest this is the only reason. Many merchants, legitimate online sellers, choose Shopify because of the higher margins, greater control, and plentiful of ecommerce tools they have access to.

To be clear, this prediction is not about Shopify being put on a counterfeit watchlist, not are we advocating for such action. We are predicting greater awareness of the issue from rightsholders, leading to greater enforcement action from vendors followed by belated marketing efforts to extol awareness of Shopify as a problematic platform. The issue is not a new issue, but we expect renewed interest following FakeSpot highlighting some of the brand risks posed. Hopefully with greater awareness comes concerted pressure from rightsholders, leading to adjustments from Shopify to better protect intellectual property rights. Shopify’s ‘repeat infringer’ policy would certainly benefit from greater scrutiny. Merchant due diligence is another area ripe for an upgrade.

Automated Livestream Monitoring

At least 1 global vendor will develop an automated livestream monitoring offering which detects streams hosted by and connected to ecommerce webstores offering knockoffs. Live streaming requires live monitoring. This notion is of paramount importance during sale events, for example, Double 11 Day in China.

The reason we predict this will happen is because of the continued growth of livestreaming in connection to Alibaba, specifically Taobao, the biggest ecommerce website in the world. Taobao has live streaming integrated so merchants can stream enabling customers to purchase directly from the stream, using Alipay. Frictionless commerce, without ever leaving the Alibaba ecosystem. There are competition law issues for Alibaba, Alipay, Tencent, and others currently unfolding in China, an issue with potentially fundamental changes in the ecommerce and digital payments market in China.

Alibaba spend considerable resources to build automation tools to remove counterfeits, with market leading image matching technology. Brand protection vendors also invest time and resource into enforcing infringing listings across Alibaba platforms for their clients. However, livestreaming is one of the key methods sellers employ to avoid detection on Taobao; from both Alibaba’s own ‘proactive monitoring’ and brand protection vendors reactive enforcement. Infringers have also adapted to this new norm; creating listings with no terms, features, images, or any other reason to raise the suspicion of automated triggers or be enforceable by a rightsholder. During the livestream viewers directed to the enforcement-resilient listing to purchase knockoffs displayed during the stream.

We recommend an intelligence-based approach. Developing intelligence mandates monitoring suspicious merchants, when doing so, livestreams can be identified ahead of time and monitored for infringements. Brand abusers who employ such tactics are normally very agile in avoiding traditional detection methods and can only be pursued when applying an investigative approach which fully assesses the nature of their operation. Vendors will, at some point, automate parts of this process to aid the intelligence-based approach, through monitoring merchants with livestreams and even capturing video evidence. Ideally, listings previously considered non-suspicious will be re-evaluated in light of this trend, with new parameters set to detect ‘shell listings’. Of course infringers will again adept their behaviour, but by taking action rightsholders will not only recapture sales, they will protect a digital touchpoint which injects vibrancy and delight into the profitable Chinese ecommerce scene.

Brand Protection vs Cybersecurity

As discussed in Part I, we was wrong in predicting certain digital risks being integrated with brand protection. Again, we reiterate our hope in 2021 “Over the next year we will see brand protection strategies assimilating more widely applicable services, such as digital risk profiling and social media auditing to deliver greater value”. This year, scorned by our previous disappointment, we predict the opposite will happen. Security concerns which also impact brand assets – therefor falling into the scope of illicit activity a brand protection investigator should monitor – will move further out of the brand protection sphere. Brand enforcement services will be repackaged with a cybersecurity slant. Because the margins are higher for issues remediated under the umbrella of cybersecurity, far higher compared to brand enforcement.

Online monitoring has turned fully in favour of automated all-in-one solutions. See Digital Brand Protection for a discussion on this trend, and the pitfalls encountered when trying to fully automate digital monitoring and enforcement services. Irrefutably, most rightsholders benefit from having access to some degree of automation. Automation done well brings significant efficiency savings, enabling greater value to be extracted from digital brand protection activities. Rightsholders have seen ‘cost per issue’ go down, albeit as the increases in scale make online brand protection more expensive than ever.

To turn the tide of falling margins, vendors will decouple certain brand enforcement services from brand protection. Those being the services which overlap to some degree with cybersecurity. For example, outbound phishing scams abusing intellectual property rights. Whilst such issues are in a grey area – sometimes dealt with within the remit of brand enforcement, and sometimes not – they will fall into the exclusive domain of cybersecurity services. Vendors of brand monitoring and enforcement services will still remediate such issues, but at a higher rate than purely intellectual property related issues. Whether the rate is justified depends on your point-of-view.

To be clear, most, security issues are not within scope of brand enforcement. The fields are distinct and require different skillsets. However, where there is overlap rightsholders always benefit from an integrated strategy, applying an investigative framework to develop intelligence and accurately risk assess threats; regardless of whether purely a threat to brand assets or a threat overlapping with a degree of cybersecurity.

I remember attending a conference in 2019, chairing a panel discussing the interface between brand protection and cybersecurity. The cybersecurity professionals all argued for greater integration between the teams whilst the brand protection professionals argued the opposite. It seems whilst the brand protection professionals may have won the debate, it will be the cybersecurity vendors with an offering which includes an IPR protection element who won commercially.

Discourse on Discord

Discord will enter the consciousness of rightsholders. Encrypted instant message app Telegram has long featured as a priority for rightsholders, in 2021 others, including Discord will join the list of monitored messaging platoforms. Significant file-sharing occurs on Telegram, as well as groups created for the sole purpose of disseminating pirated content. The same can be said of Discord, and a few other messaging apps for that matter. For a start, Discord servers advertised publicly as spaces for piracy in clear violation of Discord’s terms of service must be tackled. The longer-term challenge will be monitoring private servers engaging in piracy.

Competition Law Blunted

The UK will take a more permissive approach to competition law than our EU and US counterparts. Somewhat of a wild prediction it may sound from the outset, for 3 reasons: 1) July 2020 the Competition and Market Authority (CMA) released a final market study on regulating online platforms and digital advertising requesting tougher enforcement measures;[xxi] 2) the rest of world is taking a less permissive, more pro-enforcement stance, including as mentioned, the EU[xxii] and US,[xxiii] and China;[xxiv] 3) competition law moves at a barely perceptible pace, changes are played out over the course of years.

Competition law and intellectual property law are natural rivals. Intellectual property is monopolistic in nature. Competition law is anti-monopolistic in nature. Competition law sets out to protect consumers through the prevention of anti-competitive market structures or post facto enforcement against abuses of monopoly positions. The prevention mechanism largely manifests in the form of takeover blocking, for example the action taken to stop Sainsbury’s-Asda merging.[xxv] Post facto enforcement measures are often hefty fines handed out after an investigation into specific bad practices, for example, the £8 million fine issued to H.J. Enthoven Ltd and £1.5 million fine issued to Associated Lead Mills Ltd for entering into price-fixing and non-compete arrangements.[xxvi] Very traditional use cases for competition law.

EU competition law on the other hand has a different origin point – that of protecting the single market. The European Commission takes a particularly dubious view of IPRs in establishing local monopolies, ensuring the integrity of the Single Market takes precedence over the freedom of contract doctrine. At an EU level the overriding economic objective is ensuring the integrity of the Single Market, often wrapped up as consumer welfare. It must be said the objectives of protecting consumers and protecting the Single Market are not mutually exclusive, in fact they often go hand-in-hand to reinforce one another. By preventing market segmentation consumers have greater access to goods and services, generally lowering prices, providing more choice, and all the other benefits associated with increased market competition.

In the AB InBev beer trade restrictions case,[xxvii] the world’s largest brewer was fined over €200 million for breaching EU antitrust rules. In explaining the decision the Commissioner stated, “Attempts by dominant companies to carve up the Single Market to maintain high prices are illegal”. Illegal market segmentation was through practices such as changing the beer can size and design to be less appealing to the Belgium market. Removing French from cans was another stated anti-competitive practice, because of course everyone reads the product details before sipping their beer. Other more traditional anti-competitive practices were also part of the judgement, for example, provisions restricting distribution. AB InBev shows the fact-specific approach taken to competition law in order to protect the Single Market. Commissioner Vestager analysed the purpose behind the beer can design changes and then the negative consequences such measures could cause. This is a departure from the strict economics approach many competition authorities grapple with, which has left most of them struggling to cope in applying effective antitrust measures to the digital economy.[xxviii]

January 2020, the UK Court of Appeal handed down a judgement confirming the strict EU approach to competition law in the Ping case.[xxix] In accordance with EU competition law, stemming from the protection of the Single Market approach, the court confirmed that an outright ban on online distribution amounted to “a restriction of competition by object” without sufficient justification. Ping is a golf equipment manufacturing company, operating in a highly competitive market. There was no assertion Ping operated a monopoly, on the contrary, as the breach was ‘by object’ there was no need for an assessment on the issue. Further, it was accepted by the court Ping acted in good faith, believing the ban on online sales was pro-consumer. Ping golf clubs were restricted to physical sales in order for a trained professional to assist the buyer in purchasing the most appropriate equipment for their needs. Given the technical nature of the sport and significant variation in technology available in golfing equipment, Ping argued the prohibition on online sales was legitimate. The CMA disagreed, the court sided with the CMA based on the established body of EU law, including Coty[xxx] and Pierre Fabre.[xxxi] The court concluded less restrictive measures than an outright ban could have fulfilled Ping’s commercial objectives and therefore the ban was a breach of competition law. It is doubtful the CMA would have started enforcement action in such a highly competitive market on these grounds if not for EU precedent on the matter. Many commentators saw the approach in Ping as EU-centric and outside the traditional pragmatic approach taken by the UK. As put by law firm Latham & Watkins:

“Enforcement action against online sales restrictions is considered to be necessary in order to promote and preserve the single market imperative in the European Union. It remains to be seen whether the CMA will liberalise its approach to online sales restrictions following the end of the transition period (which is currently set to end on 31 December 2020).”[xxxii]

Will the UK turn back the hands of legal precedent? We think so, yes. Whilst Ping remains binding precedent in the UK it is hard to see how such a decision could now be rationalised. Looking towards the US, manufacturers – including Ping – regularly engage in such activities based on preventing brand or goodwill harm. Or on the contrary, as measures designed to promote competition. The US approach appears to be the more fitting model for the UK, by way of balancing out what is now a market with more trade restrictions than the past 50 years or so.

On this basis, brand owners will have greater flexibility in the UK in terms of distribution and market segmentation. Breweries will even be able to sell beer cans without French product information in the UK. UK products will be policed in the EU through measures protecting against parallel imports from outside the European Economic Area. However, parallel imports into the UK from the EEA will not be prevented, as things currently stand.[xxxiii] An increased ability to control distribution channels is largely a win for rightsholders. Consumers on the other hand lose out from the AB InBev shield, potentially leading to higher prices charged by companies with a dominant market position. The loss of Ping type cases is unlikely to impact consumers given the market was already highly competitive. In short, with the CMA no longer tied to the policy of protecting the Single Market, the emphasis can move back towards enforcement action against abuses of dominant market positions.

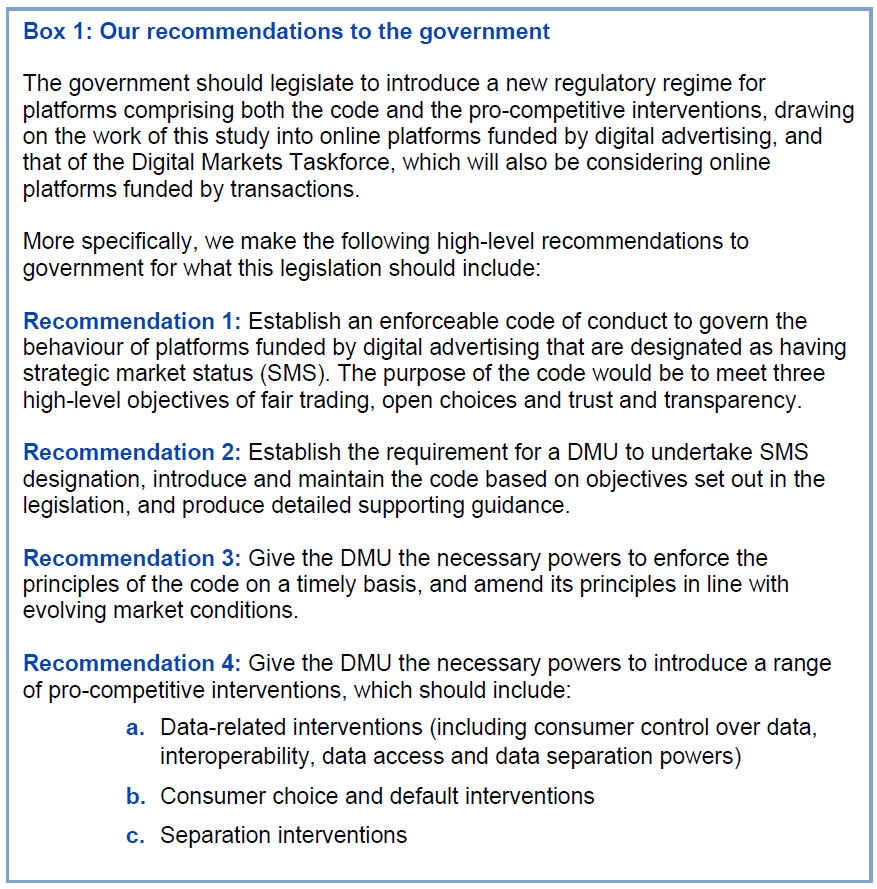

Leading back to the 437 page ‘Online platforms and digital advertising’ market study produced by the CMA and published in July 2020. In fact 2020 had a lot going on for the CMA, with trust buster Tyrie being at the centre. Tyrie is a House of Lords member, former MP, and was up until September the CMA Chairman. He spearheaded a more interventionalist approach to competition regulation, including the previously mentioned blocking of Sainsbury’s-Asda merger. Around March 2020 Tyrie called for increased enforcement powers for the CMA, to adequately equip the organisation for the digital economy.[xxxiv] The July report proposes a newly formed Digital Markets Unit (DMU) to fill the gap, 2 months later, Tyrie stood down as Chairman stating: “I now want to make the case more forcefully for legislative and other reform – in parliament and beyond – than is possible within the inherent limits of my position as CMA Chairman”.[xxxv] The proposed DMU was not the sea-change Tyrie was pushing for. A 400+ document doing little to enhance the position of the CMA or its ability to affect change.

Google and Facebook are front and central to the report. Little more needs to be said of the market dominance and power of either company. None of the recommendations set out provide adequate power for the DMU, whether it forms part of the CMA or as an independent entity, to regulate markets.

Recommendation 1 focuses on fair trading, open choice, and trust. Conceptually this reads well, but there is no meat on the bones. The main recommendations are concerned with users having greater ability to control their data, interoperability, and the like. These measures have already been applied by Google and Facebook. An outdated recommendation which has already demonstrated little real-world benefit to internet users.

Recommendation 2 and 3 broadly state the scope and powers the DMU should be endowed with. Regulation requires enforcement power, as a right without the ability to remediate a breach is no right at all. Creating a new body, or renaming part of the CMA is a good branding exercise, signalling a change in direction in competition regulation. However, in response to these recommendations the government stated “Careful consideration will be given to the nature of the new DMU powers and the interactions between these and existing elements of the regulatory landscape.”[xxxvi] – hardly a rallying call for a more aggressive stance towards competition policy.

Recommendation 4 is most noteworthy, specially 4c “Separation interventions”. These interventions come in various types, from intra-company data firewalls to complete separation. A data firewall would prevent Google from engaging in self-preferential treatment when they compete in markets they are also the dominant supplier. Complete separation for example would be to force Facebook to spin off Instagram, recognising the acquisition led to a monopoly position causing harmful market distortions. In response to the only recommendation calling for real enforcement powers the government stated:

“We agree that pro-competition measures have the potential to tackle the underlying sources of market power and positively transform innovation and growth in the digital economy. The Government agrees in principle with giving pro-competition powers to the DMU. However, these interventions are complex and come with significant policy and implementation risks. More work is required to understand the likely benefits, risks and possible unintended consequences of the range of proposed pro-competitive interventions. The Government will continue to consider this, taking into account the advice of the Taskforce, our findings from the National Data Strategy consultation, and views of stakeholders.” (emphasis added)

Whilst the government agrees competition has a positive impact on innovation and growth, they don’t want to implement the most pro-competition policies. Significant policy risks is a reference to future trade relations with the US. Now, the UK is stranded, without the backup of the European Commission and without the effective ability to regulate against the most dominant companies in the digital economy. However, actions taken in the EU, and in the US, will indirectly benefit the UK.[xxxvii] Therefore, it is presently in the UK’s interest to avoid controversial antitrust stances. The CMA has lost its spearhead, and is left with a watered-down market study, followed by further dilution from the government response – predicting a more permissive approach to competition regulation over the comings years is a no-brainer.

There we have it, 7 predictions for 2021. We look forward to seeing you next year for our recap and fresh round of predictions. Happy new year!

Further reading:

[i] https://www.theverge.com/2020/2/4/21121370/youtube-advertising-revenue-creators-demonetization-earnings-google

[ii] https://www.forbes.com/sites/natalierobehmed/2018/12/03/how-youtube-star-logan-paul-made-14-5-million-amid-scandal/

https://medium.com/@Vluff/top-10-youtubers-with-their-own-fashion-brands-643fb6d6b7de

[iii] https://www.fool.com/investing/2019/05/14/why-spotify-is-investing-500-million-on-podcasts.aspx

https://medium.com/swlh/this-is-what-it-costs-to-get-free-podcasts-from-spotify-fab3ec255753

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/06/business/dealbook/spotify-gimlet-anchor-podcasts.html

[iv] https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/podcasts-destroying-music-businesss-potential-growth-926536/

https://medium.com/swlh/this-is-what-it-costs-to-get-free-podcasts-from-spotify-fab3ec255753

[v] https://www.theverge.com/2020/7/16/21326360/michelle-obama-podcast-spotify-release-date

[vi] https://www.theverge.com/2020/5/19/21263927/joe-rogan-spotify-experience-exclusive-content-episodes-youtube

[vii] https://www.theverge.com/2020/6/17/21294863/kim-kardashian-west-spotify-exclusive-podcast-innocence-project-deal-announced

[viii] https://www.theverge.com/2020/12/15/22176014/prince-harry-meghan-markle-podcast-spotify-exclusive-archewell-audio

[ix] https://www.wsj.com/articles/spotify-strikes-exclusive-podcast-deal-with-joe-rogan-11589913814

[x] https://www.theverge.com/21265005/spotify-joe-rogan-experience-podcast-deal-apple-gimlet-media-ringer

[xi] https://variety.com/2019/digital/news/spotify-shuts-down-artist-direct-upload-1203256886/

[xii] https://www.theverge.com/2020/8/26/21403282/joe-budden-spotify-exclusive-leaving-host-podcast

[xiii] https://www.forbes.com/sites/korihale/2019/12/09/jay-zs-return-to-spotify-could-be-the-nail-in-tidals-coffin/

[xiv] https://www.theguardian.com/music/2017/jun/09/shaken-it-off-taylor-swift-ends-spotify-spat

[xv] https://www.theverge.com/2020/9/29/21494284/spotify-michelle-obama-podcast-release-exclusive

[xvi][xvi] https://github.blog/2020-11-16-standing-up-for-developers-youtube-dl-is-back/

[xvii] https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/press/index.cfm?id=2225

https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2020/december/tradoc_159183.pdf

[xviii] https://www.worldtrademarkreview.com/brand-management/drop-shipping-sites-are-flooding-influencers-counterfeit-goods-what-brands-should-do

[xix] https://www.ft.com/content/0280592d-0adf-4dcb-a831-4f8a85f414bc

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-55420445

[xx] https://www.ft.com/content/c72ae0f0-c036-11e9-b350-db00d509634e

[xxi] https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/online-platforms-and-digital-advertising-market-study

[xxii] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_18_4581

https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_19_1770

[xxiii] https://www.vox.com/recode/2020/10/6/21505027/congress-big-tech-antitrust-report-facebook-google-amazon-apple-mark-zuckerberg-jeff-bezos-tim-cook

[xxiv] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-12-14/china-fines-alibaba-tencent-for-flouting-rules-in-past-deals

[xxv] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/cma-blocks-merger-between-sainsburys-and-asda

[xxvi] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/cma-issues-fines-of-over-9m-for-roofing-lead-cartel

[xxvii] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_19_2488 https://ec.europa.eu/competition/elojade/isef/case_details.cfm?proc_code=1_40134

[xxviii] https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5785&context=ylj

[xxix] https://www.bailii.org/cgi-bin/format.cgi?doc=/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2020/13.html

https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/sports-equipment-sector-anti-competitive-practices

[xxx] https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2020-04/cp200039en.pdf

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/steven-ustel_intellectualproperty-activity-6651637376588230656-eUIb

https://ipkitten.blogspot.com/2017/12/coty-distribution-agreements-and-luxury.html

[xxxi] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:62009CJ0439&from=EN

[xxxii] https://www.latham.london/2020/03/competition-law-and-online-sales-restrictions-uk-court-of-appeal-judgment-in-ping/

[xxxiii] https://www.gov.uk/guidance/exhaustion-of-ip-rights-and-parallel-trade-after-the-transition-period

[xxxiv] https://www.ft.com/content/d528a206-5d56-11ea-b0ab-339c2307bcd4

[xxxv] https://www.ft.com/content/b48caaa5-a12d-42d8-98fd-38b71623843a

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/jun/18/andrew-tyrie-quits-uk-competition-watchdog

[xxxvi] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/government-response-to-the-cma-digital-advertising-market-study

[xxxvii] https://truthonthemarket.com/2020/12/16/building-the-digital-future-can-the-eu-foster-a-dynamic-and-crime-free-internet/