The American Dream vs Alibaba’s Global Dream

The Alibaba Group, the protagonist of China’s trillion-dollar ecommerce industry, is poised to step out from local incubation into Amazon territory. Amazon’s vast digital empire has been accumulated through the relentless pursuit of market share – even at the expense of profit. Is Alibaba’s ‘globalisation strategy’ the biggest threat to Amazon’s position as the world’s largest ecommerce platform?

Amazon recently announced it will be withdrawing completely from its local ecommerce offering in China, although limited coverage is provided through the Amazon Global Store. Unfortunately, this retreat from Amazon means Chinese ecommerce is now another arena the two conglomerates do not directly compete against one another.

The statistics appear to show a global duopoly; two ecommerce platforms dominating digital sales and exerting sway over the direction of online shopping. However, the two spheres exist without competing (or even colluding). The global giants of ecommerce have proved that the internet has not created a digital market without borders. Instead of a global duopoly, what has emerged is two segregated markets, each with its own localised monopoly, carefully bounded and tethered to their geographic realm of influence. Competition between the two so far is best described as an international stare-down with scattered attempts of encroachment.

How To Build An Ecommerce Monopoly

Language, logistics and legal environments are the obvious factors behind the segregation, however, in the digital age, the key to market dominance is brand building through cultural understanding and then achieving scale through data driven innovation and integration.

The west’s monopoly – Amazon

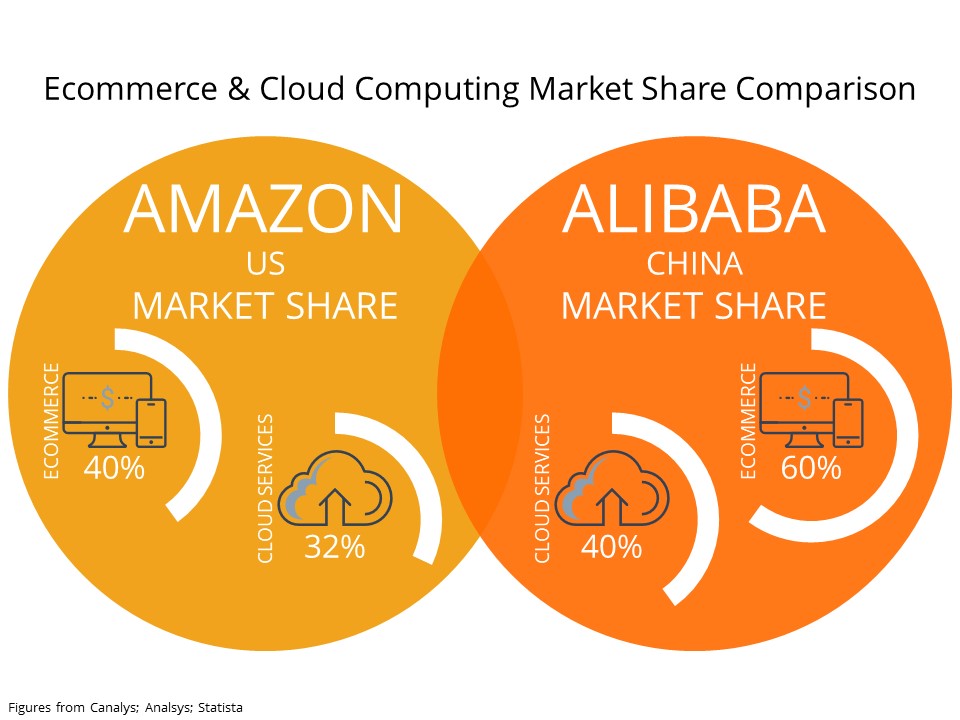

Amazon controls two key areas, ecommerce and cloud computing through Amazon Web Services. AWS has scaled phenomenally well, not only becoming the clear market leader for cloud services but also being a hugely profitable business area for the company. Ecommerce growth was achieved in market share and gross merchandise value sold, but was not a profitable business area, often times as a loss leader. Flagship programs, including Amazon Prime sustained losses for many years, in an attempt to achieve customer-platform lock-in.

As customers have already paid their monthly subscription, they perceive ordering from Amazon as almost mandatory to achieve a return on investment from the membership fee. Consumer behaviour is not always as rational as economists model it to be. Amazon Prime members now turn to Amazon for all their shopping needs without considering any alternatives – a ‘shopping reflex’ – rather than informed purchasing decisions.

In the US it is estimated Amazon accounted for 35-45% of all online sales in 2018. Forecasts differ on whether Amazon’s US market share will increase or decrease in 2019. Regardless, the data from sales, product searches and time spent across their platforms provides unrivalled insights into consumer behaviour to analyse. With such intimate knowledge of their customers, Amazon can excite and direct purchasing decisions through developing innovative and customised offerings. Combined with Echo devices featuring your very own Alexa personal assistant and it is clear Amazon has already transformed from being an ecommerce platform into an integrated ecommerce ecosystem.

Leveraging data analytics enables failing search terms to be identified i.e. search terms with low engagement leading to potential customers ‘pogo-sticking’ and ultimately, low rates of conversion. Understanding the points of failure is vital to sustaining the ecosystem, as any unmet customer demand erodes the lock-in effect. The assumption is, gaps in product lines with existing demand, as measured by search volume, leads to customers turning to other platforms or googling for the product.

The Amazon homepage dedicates around 50% of real estate to customised products, services and offers based on previous purchasing decisions, items in wish lists, items left in basket, items viewed etc. The other half of the homepage is split between generic ads and Amazon self-promotion, i.e. Echo devices or content exclusively available through Prime Video. The goal is clearly cross-selling through highly customised ads to maximise spend-per-customer and keeping customers firmly inside the grip of the ecosystem.

You can check out anytime you like,

But you can never leave!

Hotel California by the Eagles

Customers with purchasing intent not being converted is the monopoly’s ultimate anathema. Amazon’s response is either to introduce the product into the market through its own house brand –AmazonBasics, or “stealing” sellers from eBay to plug the demand. If the data used to identify products with a supply shortage was released to existing platform merchants, it is likely the demand would be met on Amazon indirectly through Alibaba via dropshipping.

However, with its own brand, Amazon has been accused of going beyond merely finding under supplied product categories and fulfilling customer demand. Critics claim a far more insidious practice of obliterating competitors within generic product categories; utilising platform analytics to identify growth categories without bearing the risk of bringing the product to the market. With Amazon’s economies of scale advantage they can quickly produce a cheaper variant or subsidise through Amazon Prime or simply benefit from privileged listing placement – the opportunity for abusive behaviour cannot be underestimated.

Whilst such tactics are potentially anti-competitive, its common practice across the tech giants, from Google to Tencent to use an integrated structure to extract preferential value from markets they dominate. Without the first mover advantage or innovative approach to ecommerce in China, Amazon never built up (or purchased) the necessary customer base; combined with a lack of localised understanding of consumers meant a customer-centric ecosystem could not be built to compete with Alibaba. What stimulates the Chinese consumer has proven to be very different to what drives purchases in Amazon’s main markets, and no one has developed a more scalable understanding of consumer behaviour in China than Alibaba.

In many ways, China’s ingrained restrictions on foreign companies entering their domestic market created this model – for every US Google a Chinese Baidu sprang up. Facebook and many other US tech companies which dominate screen-time in the west have been locked out of China. The other US ecommerce success story – eBay – went the same way as Amazon in China, famously being defeated by the then upstart Alibaba. Eventually eBay withdrew after failing to replicate their domestic success. This now appears to be a more fundamental shift away from auction sites, as eBay’s market share also dwindled in the US. Amazon stamped out competition through consistent low prices and rapid delivery. Why wait to see if your bid was successful when the product could already be delivered through Prime. As eBay fell away, Amazon and Alibaba have grown so dominate they are synonymous with ecommerce in their domestic market and enjoy a level of reverence as national champions of success.

Alibaba: The Amazon of China?

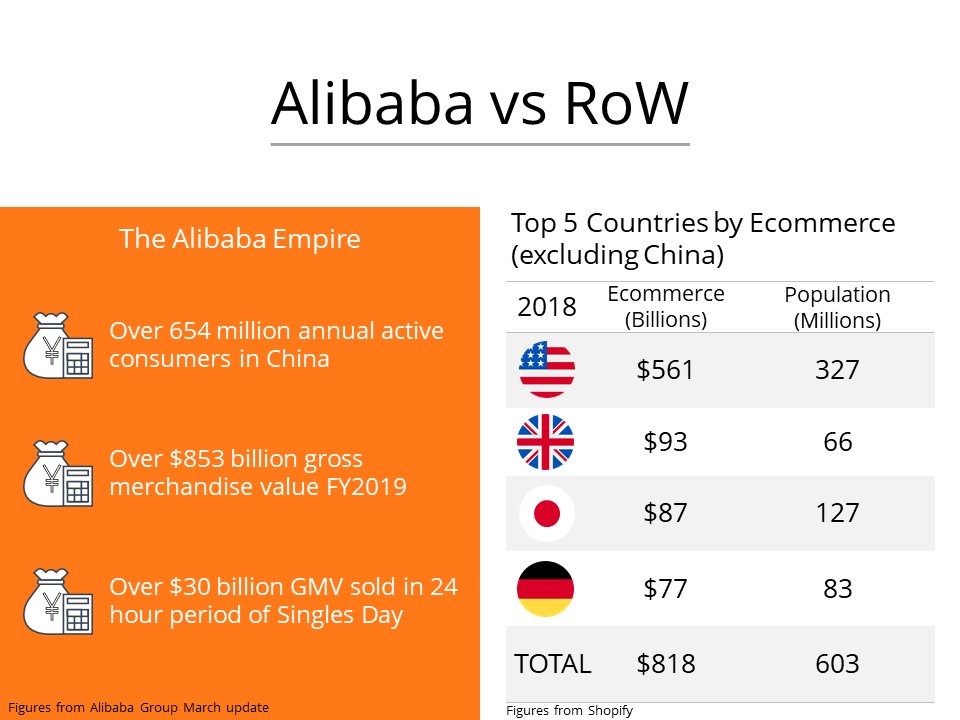

Alibaba leads the Chinese market in both ecommerce and cloud computing – therefore the comparisons with Amazon are easy to understand. Alibaba ecommerce platforms account for around 60% of ecommerce in China and Alibaba Cloud has over 40% market share in China. This makes Alibaba more dominate in both areas in comparison to Amazon in the US – in terms of market share.

Chinese ecommerce is already eclipsing the US market, with forecasts for it to grow twice as large as the US ecommerce market by 2022. However, China’s enterprise cloud market is nascent, with the US cloud computing market significantly bigger, most pronounced in the enterprise cloud services sector. In a reversal of Amazon’s model, Alibaba currently extract value from ecommerce to invest in cloud computing as Chinese companies slowly undergo the transition to cloud-based services.

Where China falls behind in enterprise cloud services market, it more than makes up for in a modern, digital financial services market. Alibaba’s related company Ant Financial, now owner of Alipay, controls over half the mobile payments market in China and is undergoing rapid international expansion.

Alipay’s leading position is another example of how tech companies leverage integration to achieve market dominance. With Alibaba’s leading ecommerce platforms Taobao and Tmall both preventing users from checking-out using payment service offerings from domestic tech giant nemesis – Tencent. Tencent’s own integration of payment services through super app WeChat has created a duopoly, with the two companies controlling over 90% over the Chinese market.

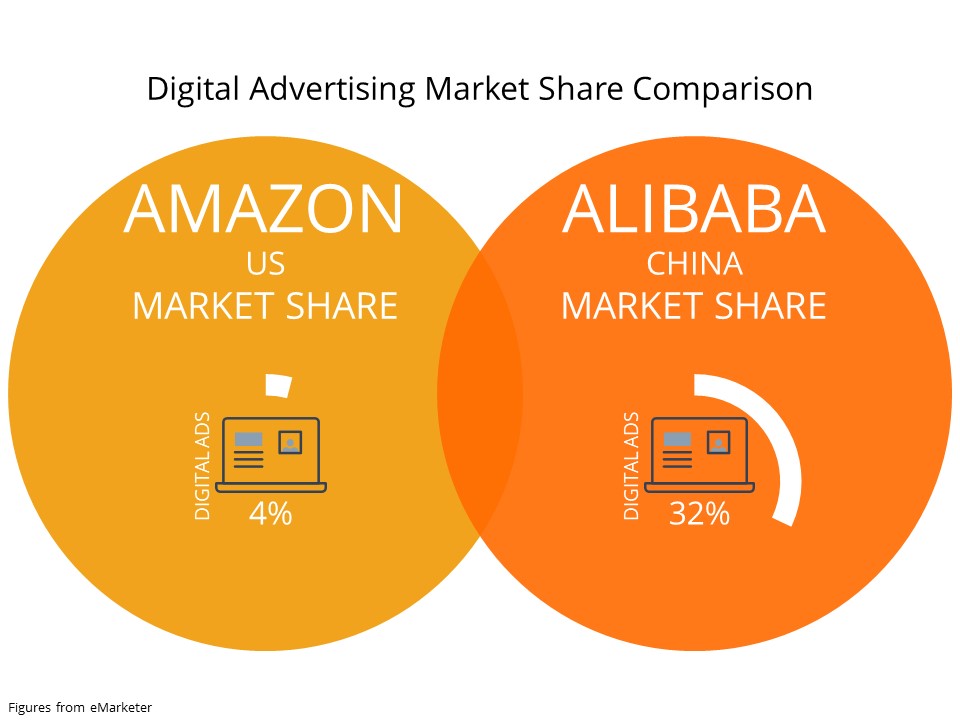

The other area Alibaba is far ahead of the curve compared to Amazon is in digital advertising. Alibaba is also the leading digital advertising provider in China. Amazon lags behind Google and Facebook in the US, with around 5% of the total market. However, with both Google and Facebook coming under domestic pressure for increased transparency within the digital ad supply chain, Amazon is attempting, with some success, to seize the opportunity to grow this business area.

Both Amazon and Alibaba are investing heavily into integration with logistics partners and attempting to ‘in-house’ the entire supply-chain process. Both are investing into digital content, as a platform provider and a content producer. And both are investing into ambitious space technologies.

Back down to earth, Alibaba’s ecommerce business requires a closer look, as it differs from Amazon and more generally with how ecommerce is done in the west. Jack Ma, Alibaba’s visionary founder has stated on many occasions that the aim is to be a global company, but the model does not directly compete with Amazon or eBay. Alibaba’s goal is to create tools which enable businesses by removing points of friction in the market. Alibaba does not manufacture or sell any products; unlike Amazon, which directly competes with its own merchants.

Integration with payment services enabled greater trust across the Alibaba ecosystem, as payments are held in escrow as part of the fulfilment process. Not only generating trust in online sales, a fairly recent transition in which some markets now take for granted, but also building a seamless transaction from capturing customers to taking payment. This removes an intermediary from Amazon’s equivalent 1-click ordering, extracting greater value for Alibaba in the process.

The Alibaba Group Ecommerce Platforms

Taobao – the world’s largest ecommerce website has more annual active users than the entire population of the United States, United Kingdom, Japan and Germany combined – the top 5 countries by ecommerce sales, excluding China. Taobao facilitates C2C transactions, focusing on the domestic market, providing the tools for individuals to create their own store and mini ecommerce empire. The homepage is bright and busy, a whirlwind of orange and ads with an experience highly optimised for mobile viewing through the app. Search results are renowned for delivering results customised perfectly to the user and with almost endless amounts of product choice.

Tmall – the domestic B2C arm of the Alibaba Group and home to the leading local and global brands in China. Tmall is only second to Taobao in terms of sales, directly competing with Chinese rival JD.com in providing a more curated shopping experience for customers. Merchants are subject to stricter vetting and higher selling fees, although Tmall Global enables entities not registered in China to sell to Chinese customers.

1688 – the domestic wholesale arm of the Group. New Taobao sellers often start by sourcing suppliers through 1688, applying a small mark-up for the consumer market.

Xianyu – Alibaba’s domestic “recommerce” platform for pre-owned items.

Alibaba and AliExpress – “Alibaba.com” was the original platform created by Jack Ma with the aim of connecting Chinese sellers to the global market, operating as a B2B platform. AliExpress operates similar to Alibaba, with many sellers using both platforms, however, AliExpress generally enables purchasing of smaller quantities and therefore targets both businesses and consumers. With low prices and often no minimum order quantity (MOQ), AliExpress has become the go-to platform for dropshippers.

Alibaba’s international expansion effort so far has been to invest in successful ecommerce platforms in strategic location, including Lazada across south-east Asia, Tokopedia in Indonesia and Snapdeal in India. But now, AliExpress, one of the Group’s core platforms is undergoing a transformation – merchants from Russia, Turkey, Spain and Italy will be eligible to sell their wares internationally, excluding China. Enabling foreign merchants on a core Group ecommerce platform is a shift away from the old business model, and more importantly, is a direct challenge to Amazon.

‘From Local To Global’

Choosing AliExpress for the expansion is significant. The platform is a core component of the Group’s ecommerce business area, achieving strong growth and already the number one ecommerce platform in Russia.

Russia

In late 2018, AliExpress formed a joint-venture with Russian conglomerate Mail.ru – owners of Russia’s leading social media platform VK. Following the Chinese model, VK in many ways was a clone of Facebook, developed to cover Russia and then becoming the social media platform of choice for nations using Cyrillic. Through the Mail.ru joint-venture, the Alibaba Group has forged a gateway into Eastern Europe and the Baltic states.

Anyone who has conducted brand protection work on VK; from monitoring counterfeits to digital rights protection, will be well aware of the scale of commercial activity occurring across the platform. Combining a large user base and social engagement with Alibaba’s ability to create frictionless shopping experiences, assuming VK follows Facebook’s pivot towards commerce, and the Alibaba Group is set for a windfall.

Turkey

The Alibaba Group has already invested into Turkey, seen as a key strategic partner. In mid-2018 the Group invested into fast growing ecommerce site Trendyol, popular with younger, tech-enabled consumers of Turkey. The country boasts strong demographics, a falling currency making inward investment cheaper and relatively low internet penetration which makes the environment ripe for growth. Amazon also launched in Turkey late 2018, hoping to benefit from the favourable demographics as a growth market.

Furthermore, the political alignment of Turkey – or more accurately, the non-alignment with US politics means it is harder for the US to undermine Alibaba’s ambitions in the region. US allies, including South Korea have experienced the economic consequences of being caught in the middle of the superpower tug-of-war. Combined with Turkey’s geolocation being a vital trade route linking Asia to Europe and Alibaba’s stated long-term aim of reducing all international shipping to under 72 hours and the investment into Turkey fits perfectly within the local to global strategy.

Italy & Spain

In both Spain and Italy, Amazon is the entrenched market leader. Entering these two countries contrasts with Russia and Turkey – or even India where both companies are trying to gain a foothold. With AliExpress entering Spain and Italy the intent is clear, to start taking market share away from Amazon.

If AliExpress can gain traction with the merchants, then it is only a matter of time before the Group expands the reaches of the program across Europe, including the mature markets of the UK, Germany and France. Unlike Amazon, Alibaba does not directly compete with merchants. The battle for the ‘Buy Box’ is never against the all-seeing overlord, only the other merchants. With enough incentive, merchants could be tempted away from Amazon. Typically, new ecommerce entrants struggle to recruit merchants away from Amazon, as US giant dominates in terms of reach. However, with AliExpress and the full force of the Alibaba Group, the balance of power could shift.

Whilst AliExpress does not directly compete with merchants, moving across Europe will not be so easy. Spanish merchants will be competing with Chinese merchants; in terms of price and access to manufacturing resources will reduce the product lines international merchants can feasibly compete on. The success of dropshipping from AliExpress highlights this fact. Other more culture-based elements may need to be adjusted, for example, AliExpress’ constant ‘coupon spamming’ may be great for dropshippers, but less so for everyday consumers outside the US – as Groupon’s global retreat has shown. Quite simply, AliExpress being open to all merchants is not enough of a shift in the ecommerce equation to usurp Amazon in key entrenched markets.

For the Alibaba Group to fully challenge in Europe and potentially even the US, they will need to acquire and localise. Having witnessed, and to some degree caused, eBay and then Amazon to withdraw from China, it is difficult to see the Group using a core platform as the sole means of entry to Europe and the US. Alibaba’s previous attempt through the creation of a new ecommerce brand – 11 Main – failed, and so any re-entry is likely to follow the Lazada model. But the US has already blocked Alibaba’s first steps into the US payments industry, blocking Ant Financial from acquiring MoneyGram in early 2018, predictably citing security concerns. It can only be assumed we will see the same US political response if the Alibaba Group was to attempt at competing directly with Amazon through purchasing a fast-growth US ecommerce platform, the likes of Wish.

An expanding giant means some ecommerce players will be swallowed to create space for the duopoly. Political environment permitting, the question becomes who can Alibaba partner with to directly challenge Amazon?

The Foundation For An Economic Cold War?

Technology companies are becoming increasingly politicised in the age of innovation, regardless of their desire to be. However, this also represents a more general trend from large US companies, after years of China being listed as the key market break into, there has been a shift towards other, potentially friendlier high growth markets such as India, Turkey and Brazil. After years of dancing around one another on the international scene, it seems only a matter of time before the largest ecommerce Group enters the world’s largest retail market. Even if that means stepping on Amazon’s toes.

It is no surprise to see the US pivoting towards protectionism given the growing threat of Chinese companies attempting to take on homegrown heroes in their own back yard. With Huawei being the most notable example, not only eating market share from the iPhone in China but entering the US with a range of competitive products, including the eerily Macbook Pro-esque laptop, the ‘Huawei Matebook Pro’.

Huawei has ended up on the Entity List in an attempt to restrain the company’s expansion, and Alibaba’s Taobao has for the third-year running ended up on the Notorious Markets List. The sharp responses contradict years of criticising China’s protectionism, but are seen as part of the wider trade war in which two nations are competing for economic, technological and political supremacy. Tech is seen as a key strategic industry that must be defended.

A flagship Alibaba project, announced with US Presidential backing, was cancelled in 2018, with Jack Ma citing escalating trade tension making the environment not conducive to international business. Alibaba’s plan was to connect US producers and merchants to the Chinese market, with an estimated 1 million jobs to be created in the US. It seems the US may have preferred the old model of segregation, at least as the lesser of the two evils.

It has become prudent for Chinese and US companies to make contingencies for complete untangling with their counterparts. Huawei started preparing for worst-case scenarios at least since early 2018, when Chinese rival ZTE was placed on the Entity List. The Alibaba Group is reportedly considering a secondary listing in Hong Kong to raise finance without any further reliance on the US capital markets. Even given the semi-autonomous position of Hong Kong, the move will inevitably be paraded by the Chinese government as a repatriation of a Chinese power.

Collision Course?

Whether Amazon and Alibaba will lock horns is difficult to predict given the current trade and technology war. Tensions between the home nations of the ecommerce giants run deep and there is still room for both Amazon and Alibaba to grow within their key markets without squaring up. Consumers may be relying on local rivals to provide any real competition and innovation in their domestic market. The trend towards social-commerce may provide some competition through Facebook and Facebook-owned-Instagram in the US and Pinduoduo in China.

If there is to be a challenge in any mature market, it seems Europe will be the arena and Alibaba the initiator. The success AliExpress has in poaching Spanish and Italian merchants may provide some indication as to whether the two monopolies remain content within their separate spheres, or set for collision.